Tariffs can make imported goods more expensive for consumers, particularly products without a strong domestic industry or those that rely on global supply chains.

That’s a main finding of analysis done by The Budget Lab at Yale, which projected the impact of U.S. tariffs on Canada, Mexico, and China and retaliatory tariffs from those countries on U.S. goods.

In that trade war scenario, electronics, cars, and clothes are among the products that would see the largest price increases for American consumers. No commodities would see a price decrease in the United States, although services and goods for which the United States has a strong domestic industry would be most insulated.

The products most impacted by a trade war with Canada, Mexico, and China

The Budget Lab at Yale, a nonpartisan research center, ran an economic analysis of how commodity prices would change if the United States imposed 25% tariffs on Canada and Mexico and a 20% tariff (which is currently in place) on goods from China on top of the tariffs that were already in place when the Trump administration took office.

The table below displays the findings of The Budget Lab’s analysis.

A few themes are apparent.

Prices increase the most in sectors that either are import dependent or rely on complex global value chains. That includes electronics and machinery, vehicles and auto parts, metals and raw materials, and apparel and consumer goods.

For example, the United States doesn’t have domestic capacity to build large amounts of complex electronic products, like laptop computers and smartphones. Those are made up of parts built and assembled around the world, largely in Asia.

Many automobile manufacturers have set up supply chains that stretch across North America. Many vehicles manufactured in North America will cross borders between Canada, Mexico, and the U.S. multiple times before final assembly. As a result, they would be subject to multiple tariffs throughout manufacturing.

Canada is a major supplier of steel, aluminum, and other raw materials for the United States, as are Mexico and China to a lesser extent.

The United States has very limited domestic apparel and consumer goods industries, meaning those sectors are also exposed to tariffs.

Tariffs on Canada, Mexico, and China would have a mixed impact on agricultural commodities and energy. Wheat and oil seeds would experience significant price hikes because the U.S. imports a significant amount of those products from Canada. That would have a downstream impact on the price of food, particularly given that agricultural products tend to have thin margins, leading producers to pass the cost of the tariffs on to consumers.

The price of imported energy is projected to increase. Canada and Mexico supplied roughly 70% of U.S. crude oil imports in 2023. Those countries are key suppliers because they produce different-quality oil that the U.S. refines. Their importance is also due to their geographic proximity to U.S. refiners and existing infrastructure like pipelines and ports.

Services would be highly insulated from tariffs on Mexico, Canada, and China. Cross-border provision of services, like business services or communication services, are generally not subject to tariffs. In some cases, service providers can rely on imported goods, but the pass-through costs to consumers are likely to be less severe.

The overall economic impact of a trade war with Canada, Mexico, and China

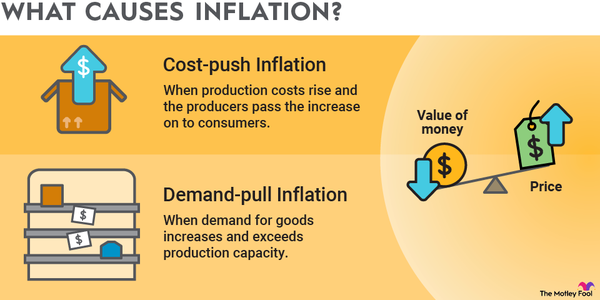

The Budget Lab at Yale projects that a 25% tariff on Canada and Mexico and a 20% tariff on China and retaliatory tariffs on U.S. exports would increase inflation and decrease U.S. gross domestic product.

Under a limited retaliation scenario, prices would increase by 1%. A full retaliation scenario, which includes reciprocal tariffs on U.S. products, would see prices increase by 1.2%. That would cost consumers $1,600 to $2,000 before they substitute and limit spending.

A trade war would reduce the disposable income of lower-income households 3 times more than it would that of higher-income households. That’s because lower income households have to spend more of their cash on consumer staples, many of which are imported. The projected added costs from tariffs hit those households harder, making tariffs a type of regressive tax.

That’s consistent with projections from the Peterson Institute for International Economics, which found that those tariffs would cost the median U.S. household $1,200 a year, even if tax cuts in the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act were extended.

Tariffs and retaliation -- limited or reciprocal -- would shave around 0.6% off of U.S. GDP in 2025 and another 0.1% in 2026 on top of that. Over the next decade, limited retaliation would reduce U.S. GDP by 0.3%, and full retaliation would decrease GDP by 0.4%, according to The Budget Lab at Yale.

Sources

- The Budget Lab at Yale (2025). “The Fiscal, Economic, and Distributional Effects of 20% Tariffs on China and 25% Tariffs on Canada and Mexico.”

- The Peterson Institute for International Economics (2025). “Trump's tariffs on Canada, Mexico, and China would cost the typical US household over $1,200 a year.”

The Motley Fool has a disclosure policy.