A credit default swap is, essentially, insurance purchased against the possibility of default. Credit default swaps became famous (or, rather, infamous) during the financial crisis of 2008-09. They’re blamed for being a leading cause of the demise of fabled investment bank Lehman Brothers and credited as the reason that a number of fortunes were made even as the global economy teetered on the brink of collapse.

Read on to learn more about credit default swaps -- their development, pros and cons, and role in the financial world.

What are credit default swaps?

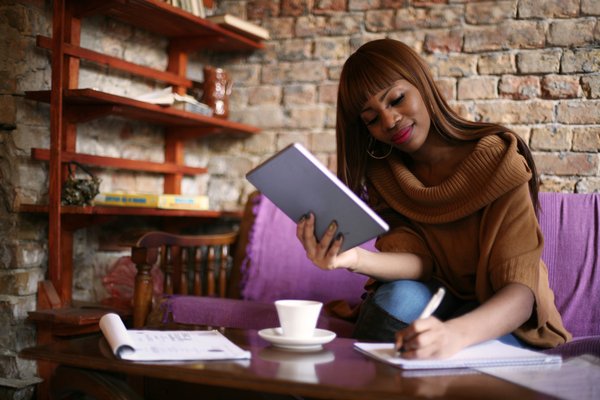

Credit default swaps (CDS) are the most common type of financial derivative, a form of insurance that protects purchasers from losing money in case of a borrower default. Banks, for example, purchase credit default swaps to hedge against potential losses by borrowers. Pension funds, insurance companies, bond holders, and other institutions also use swaps for the same reason.

The swaps were pioneered in 1994 by former JPMorgan banker Blythe Masters, who described the strategy as a means of creating “a market where you could see transparently pricing for the credit risk, and where those that had that risk could pay those that wanted that risk to assume it on their behalf, and vice versa.”

The market for the swaps took off swiftly and was worth $62.2 trillion on the eve of the 2008-09 financial meltdown.

Lehman Brothers, which had been in existence since 1844, collapsed in 2008 after its vast trove of mortgage-backed securities and collateralized debt obligations (CDOs) were revealed to contain large amounts of subprime debt. As much as $400 billion of Lehman’s debt was ostensibly covered by credit default swaps, but one of its primary insurers, American Insurance Group (AIG -1.1%) lacked the funds to cover the debt. Because of its size and importance to the global financial system, AIG required a $182 billion federal bailout.

Trillions of dollars in wealth disappeared because of the worst economic downturn since the Great Depression. Fabled investor Warren Buffett lost $3 billion during the crisis, leading him to describe derivatives as "weapons of mass financial destruction."

A few prescient investors, however, wound up with super-sized profits from the debacle. Michael Burry, portrayed by Christian Bale in the movie “The Big Short,” made an estimated $725 million for himself and his investors in Scion Capital with a bet against the subprime mortgage market by purchasing these swaps.

(Burry also would be credited with helping to launch the 2020 GameStop (GME -1.76%) short squeeze, making his firm about $100 million -- although if he had sold shares at the stock’s peak, his profits could have topped $1 billion.)

Pros and cons

Pros and cons of credit default swaps

The advantages and disadvantages of credit default swaps are fairly simple. From a positive standpoint:

- Credit default swaps protect lenders against risk. Since they’re presumably sheltered from the worst possible outcomes, financial institutions can make riskier loans that encourage creativity and innovation.

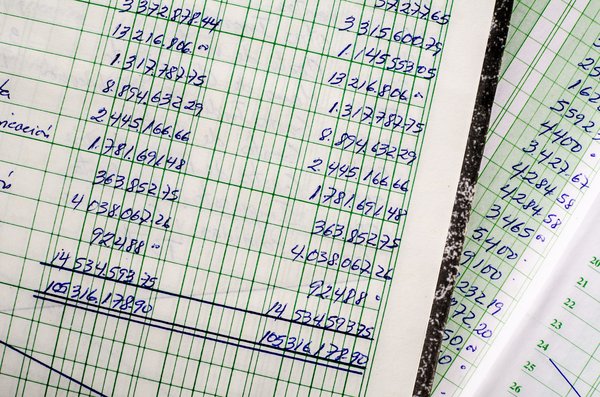

- The swaps also provide a steady stream of income. Although these swaps are generally inexpensive -- about 1% of value for an investment-grade security and 5% for a risky investment -- their purchase often represents a steady and predictable income stream for its seller.

Of course, there are downsides to credit default swaps, too:

- Until 2010, credit default swaps were totally unregulated. The lack of regulation meant that purchasers had no idea if the businesses selling swaps had enough resources to cover all possible defaults. In many cases, the firms that sold the swaps couldn’t cover the defaults during the 2008-09 crisis.

- The swaps can also provide buyers with a false sense of security, especially when it comes to riskier debt. Investors who routinely go out on a limb generally don’t fare so well on a long-term basis.

Related investing topics

CDS changes

Reforming credit default swaps

The CDS market was reformed in 2010 by the passage of the Dodd-Frank Act, a response to the financial crisis. The legislation affected swaps in three major ways:

- It created the “Volcker Rule,” named after the late chairman of the Federal Reserve System. The rule banned banks from using customer money to invest in financial derivatives such as credit default swaps.

- The Commodity Futures Trading Commission was required to create a clearinghouse for pricing and trading the swaps.

- The law phased out the riskiest credit default swaps.

Despite the reforms, Dodd-Frank didn’t make investors completely safe from the unintended consequences of CDS. In 2012, for example, JPMorgan Chase (JPM -1.47%) reported losses of more than $6 billion on its “London Whale” bet that involved a portfolio of credit default swaps.

Investors who bought troubled Greek bonds in 2012 and assumed their risk was negligible because they also purchased credit default swaps took a hit when Greece required bondholders to accept losses, rather than defaulting on the bonds and triggering payments from the swaps.