You may have heard about burden of proof on a television show or read about it in a news story; let’s just hope it was never used against you in a court. The burden of proof is the standard for a decision in a criminal or civil legal proceeding. We’ll tell you about the burden of proof -- its origins in U.S. law, its types, and an example of how it’s come into play in the financial world.

What is the burden of proof?

The burden of proof is the obligation of a party in court to show that its version of the facts is true. Although it sounds like a simple concept, it can become quite convoluted (like everything else in the legal world). Although the idea of a burden of proof is an ancient legal doctrine, dating back at least to Roman jurisprudence around 533 AD, it continues to evolve, with definitions added as late as 2009 in the United States.

Generally speaking, plaintiffs are responsible for providing the burden of proof, although defendants may raise factual issues that result in a verdict in their favor. The state (and sometimes the federal) government is usually the plaintiff in a criminal case; individuals or companies typically are the plaintiffs in civil matters. Because the stakes are so different, there are different standards for the burden of proof in civil and criminal cases.

Standards

Burden of proof standards

There are two stages of burden of proof standards: low-level standards and major standards. “Some credible evidence” is a low-level standard that’s commonly used when a quick decision is required. For example, a judge could issue a restraining order if there’s “some credible evidence” that a life is in danger. Because it’s a low standard, “some credible evidence” is often a temporary placeholder used before a final decision is made.

A second low-level example would be “probable cause,” or a reasonable belief that a violation or crime has been committed. For example, if you’ve ever been stopped by the police and asked to consent to a search of your vehicle, they presumably had probable cause to believe that you were hiding something illegal in it -- even though it’s a very low-level standard when it comes to providing the burden of proof.

The U.S. Supreme Court added a “reasonable to believe” standard in 2019 that allowed police to search a vehicle without consent after a suspect has been arrested if there’s a likelihood that evidence related to the crime could be found in the vehicle.

Major standards include “beyond a reasonable doubt.” This is generally used to prove guilt in criminal cases. It’s a higher standard, since more is at stake -- a person’s freedom or even their life, compared to the money that’s usually being contested in civil cases.

“Clear and convincing evidence” is another burden of proof standard that requires more effort than the low-level standards. It can be used in cases involving parental rights, civil liberties, wills, restraining orders, and conservatorships.

A slightly less important but commonly used burden of proof is called “preponderance.” It’s simply an argument to persuade a judge or other party that your claim is true. It’s generally reserved for civil litigation.

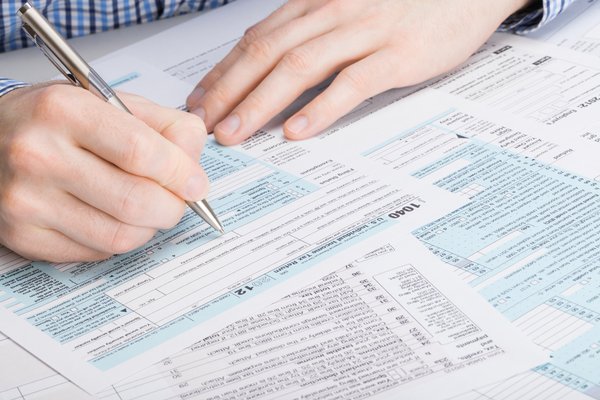

Related investing topics

Example

Example of burden of proof

One of the most complex federal investigations ever involved the 2001 collapse of energy trading giant Enron. The Houston-based company was tabbed by Fortune as “America’s Most Innovative Company” for six consecutive years, but its real innovation was accounting fraud. Investor losses were estimated to be $74 billion as a result, and sweeping legislation known as the Sarbanes-Oxley Act was passed in 2002, tightening corporate accounting rules.

Lawyers for former Enron executive Kenneth Lay, who faced six criminal counts, and Jeffrey Skilling, who was charged with 28 crimes, argued that the defendants were likely to be found innocent, since the government had a heavy burden of proof in proving wrongdoing in an extremely complicated business.

Despite the complexities of the energy trading world -- one juror described the evidence as “was like having a 25,000-piece puzzle dumped on the table” -- both men were found guilty on most of the fraud and conspiracy charges.