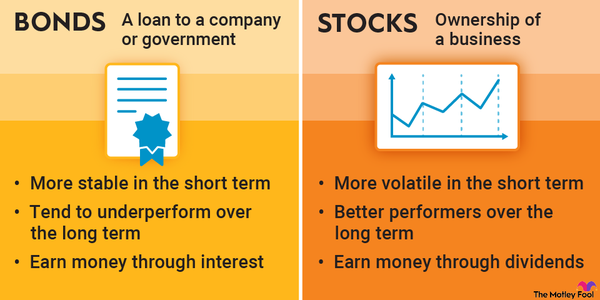

Stocks continue to be the best means of building wealth over time, but that doesn't mean bonds should be left out of your portfolio. The advantage of bonds is that their values tend to fluctuate less frequently and drastically than stock values while still offering interest income.

Bonds

Treasury bonds and corporate bonds tend to get the lion's share of attention, but municipalities -- such as states, cities, counties, and individual government entities -- issue bonds, too. There's a large market for investing in municipal bonds, or "muni" bonds. Just like their corporate and federal government counterparts, there are plenty of good reasons to add municipal bonds to your portfolio.

Here's what you need to know about investing in municipal bonds.

How they work

How municipal bonds work

A municipal bond is a debt issued by a state or municipality to fund public works. Like other bonds, investors lend money to the issuer for a predetermined period of time. The issuer promises to pay the investor interest over the term of the bond (usually twice a year) and then return the principal to the investor when the bond matures.

For example, if you invest $5,000 in a 10-year municipal bond paying 5% interest, you've lent $5,000 for 10 years. In return, the municipality will pay you $250 annually in interest -- typically in biannual installments -- and then return your $5,000 at maturity in a decade.

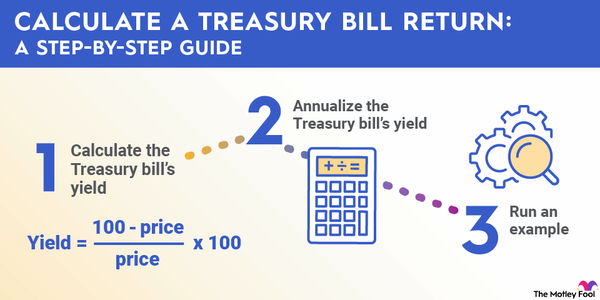

Bond values are usually more stable than stock prices, and the value is easy to calculate: It's the bond's face value plus the interest it will pay, along with an adjustment to that face value based on the difference between current interest rates and the rate the bond pays. The adjustment brings the bond's effective yield in line with what a similar issue would yield today.

In other words, if interest rates are higher today than when a bond was issued, its market value is lower because investors will earn a higher yield by buying new issues. The opposite is also true: If rates fall from the issue date, the value of existing bonds will usually rise.

However, so long as you hold the bond to maturity and the issuer continues honoring its obligation to pay you, you'll get the face value of the bond back, and the volatility of the bond value won't affect what you get at redemption.

Types

Types of municipal bonds

Municipal bonds come in two varieties: general obligation and revenue bonds. General obligation bonds finance public projects that aren't linked to a particular revenue stream. Revenue bonds, by contrast, finance public projects with the potential to generate revenue. There are advantages and drawbacks to investing in each type.

General obligation bonds

General obligation bonds are used to fund public projects, such as building a park or improving a school system. These projects include things that don't inherently make money but improve the communities they serve.

General obligation bonds are backed by the full faith and credit of the issuer, meaning they're not secured by any specific asset that bondholders could repossess. As such, general obligation bonds have traditionally been some of the safest bonds you can buy.

Revenue bonds

Revenue bonds are issued by municipalities to finance revenue-generating projects, such as a toll road or concert hall. The cash generated by the project will pay back investors in those bonds.

Revenue bonds have higher default rates than general obligation bonds because the funds are used for a specific project that may or may not be completed on time and within budget and may not generate the projected revenues. So, it's important to research the issuer's credit rating before risking your capital.

How to invest

How to invest in municipal bonds

There are three ways to invest in municipal bonds:

- New issues

- The secondary market

- Bond funds

New issues are bonds a municipality sets up for a new project. The secondary market is where you can buy bonds that are already issued from other investors or sell not-yet-matured bonds you already hold (similar to how stocks are traded). Bond funds are investments in a fund that owns bonds. You own a stake in the bonds via your ownership of that fund.

In all these cases, you'll buy and sell through a broker, similar to how you invest in stocks. It's important to understand the fees you'll pay and the potential "markup" -- a selling price above face or market value -- of the bond.

Brokers who buy and sell municipal bonds are required to register with the Municipal Securities Rulemaking Board (MSRB), which governs the muni bond market. They must disclose certain pricing information so that you, as an investor, can understand what you're paying.

A mutual fund or exchange-traded fund (ETF) that invests in bonds might be appropriate as well. Your investment in a muni bond fund gives you a small stake in every municipal bond the fund owns.

The benefit is instant diversification, which can help you avoid losses from being too exposed to a single bond. The downside is potentially high management fees, along with more direct exposure to interest rate volatility in the short term, since bond fund prices are based on current market values of the bonds owned by the fund.

Pros and cons

Benefits and risks of municipal bonds

On the whole, municipal bonds have a low default rate. Between 1970 and 2015, there were just 99 muni bond defaults. Of these, only nine general obligation bonds defaulted, and not a single municipal bond issue assigned the highest credit rating defaulted.

Municipal bonds have been 50 to 100 times less likely to default than corporate bonds. However, municipal bonds are not risk-free. In recent years, some governments have defaulted on their municipal bonds, including Detroit in 2013 and Puerto Rico in 2016.

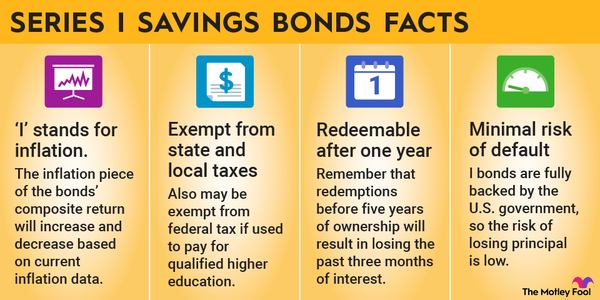

Municipal bonds generally offer lower interest rates than corporate bonds. The interest you earn is tax-free at the federal level, though it may be subject to state income taxes, particularly if the issuing municipality is outside your home state.

Keep in mind, however, that the tax benefits of municipal bonds only apply to interest payments -- not capital gains. Those gains are still taxable if you sell a bond for more than you paid.

Muni bonds also carry interest rate risk. If interest rates go up while you still own a particular muni bond, you will earn a lower yield than you'd be able to get from a new issue in the future.

Interest rate changes will affect the value of your bonds on the secondary market, too. If you have to sell a bond in the future, you may have to sell it below redemption value to compensate for the lower yield if rates go up (or for a profit if they fall). But as long as you hold the bond to maturity, you'll earn its face value back from the issuer.

Ratings

Municipal bond ratings

There are three major ratings agencies that grade bond issuers based on their likelihood of meeting their financial obligations versus defaulting on them. They are S&P Global (SPGI -1.31%), Moody's (MCO -2.19%), and Fitch.

Generally, the higher an issuer's credit rating, the lower the interest rate its bonds pay. Conversely, issuers with a lower rating generally must offer higher interest rates to offset the associated risk.

But remember that bond ratings can change. Just because an issuer starts out with a strong rating doesn't mean it can't get downgraded if its financial circumstances change, as occurred in Detroit more than a decade ago.

The good news is that muni bonds have a high rate of recovery even when they default, but investors' capital may be tied up longer than the term of the bond. Also, investors rarely recoup interest not paid. So, be sure to consider all the implications when picking which municipal bonds to buy.

Muni or corporate

Municipal bonds versus corporate bonds

Municipal bonds differ from corporate bonds in the tax treatment of the interest they pay. They also have lower default rates, making them generally lower risk. This is why municipal bonds usually pay lower yields than similar corporate bonds. Additionally, muni bonds generally require a $5,000 minimum investment, while corporate bonds start at $1,000.

In short, the risk-reward profiles for munis and corporate bonds are different. If less risk is your priority, munis come out ahead. If better yields with more risk suits you, corporate bonds get the nod. Just as with stocks, a diversified mix of risk and opportunity across assets is often the best approach.

Related investing topics

Should I invest?

Should you invest in municipal bonds?

The best bonds to invest in depend on your financial goals and situation. As with other bonds, the biggest reason to own municipal bonds is to lower the risk of losing capital in exchange for lower potential total returns. This is particularly important with funds for which you want the lowest level of risk of permanent losses or as part of a diversified portfolio of stocks and bonds.

When considering muni bonds, especially if you're comparing them to corporate bonds, don't forget to factor in the other advantages, like historically lower risk of losses and potential tax benefits that result in higher after-tax yields.

FAQ

Municipal bonds FAQ

Is a municipal bond a good investment?

Like every other asset type, it depends. Munis are generally low-risk ways to earn some yield while protecting your capital. They tend to have higher yields than Treasurys and lower risk of defaults than corporate bonds, though they also have lower yields. However, if you're after long-term wealth generation, a portfolio that includes a diversified mix of high-quality stocks will likely generate higher total returns.

How do municipal bonds work?

Like other bonds, a muni bond is a loan to the issuer. When you buy a muni -- typically in amounts of $5,000 or greater -- you are lending money to the municipality, which will pay you interest, usually twice per year, and then repay the face value to the bondholder when it matures.

For example, if you invest $5,000 in a 10-year muni with a 5% yield, you'll get a $125 interest payment twice a year, and when the bond matures in a decade, you'll get your $5,000 back (assuming the issuer doesn't default).

In the case of a default, bondholders are very close to the front of the line of creditors to be repaid. It may take longer, but bondholders generally recoup a significant portion of the amount they invested, even in a rare municipal failure.

What is the average return on municipal bonds?

According to S&P Global's Municipal Bond Index, the average yield to maturity is 4.04%, with a tax-equivalent yield (remember, muni interest payments are exempt from federal taxes) of 5.75%, as of Jan. 7, 2025.